Most of the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal waters are listed as impaired because of excess nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment. These pollutants cause algae blooms that consume oxygen and create “dead zones” where fish and shellfish cannot survive, block sunlight that is needed for underwater Bay grasses, and smother aquatic life on the bottom. The high levels of nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment enter the water from agricultural operations, urban and suburban stormwater runoff, wastewater facilities, air pollution and other sources, including onsite septic systems. Despite some reductions in pollution during the past 25 years of restoration due to efforts by federal, state and local governments; non-governmental organizations; and stakeholders in the agriculture, urban/suburban stormwater, and wastewater sectors, there has been insufficient progress toward meeting the water quality goals for the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal waters.

Source: Chesapeake Bay TMDL Executive Summary

The Chesapeake Bay TMDL establishes standards for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment for 92 separate segments of the 64,000-square-mile Chesapeake Bay watershed. The Port Tobacco River is one of those segments (POTOH2_MD).

Thousands of previously approved TMDLs have been established to protect local waters across the Chesapeake Bay watershed. For watersheds and waterbodies where both local TMDLs and Chesapeake Bay TMDLs have already been developed or established for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, the more stringent of the TMDLs will apply. In some cases, the reductions required to meet local conditions shown in existing TMDLs may be more stringent than those needed to meet Bay requirements, and vice versa.

The Bay TMDL sets annual standards for nitrogen and phosphorus for the Port Tobacco River that are significant reductions over the average-flow standards set in the Port Tobacco River TMDL in 1999. (No Port Tobacco River TMDL was established for sediment at that time.) Low-flow standards set in the Port Tobacco River TMDL are still in effect.

Excessive nitrogen and phosphorus in the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries promote a number of undesirable water quality conditions such as excessive algal growth, low dissolved oxygen, and reduced water clarity. The effect of nitrogen and phosphorus loads on water quality and living resources can vary considerably by season and region.

Sediment suspended in the water column reduces the amount of light available to support healthy and extensive submerged aquatic vegetation or underwater Bay grass communities. Sediment also can contain other pollutants. For example, certain bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli) often cling to sediment. By reducing sediment, reductions in phosphorus delivered to the Bay (and possibly other pollutants such as E. coli) also will occur.

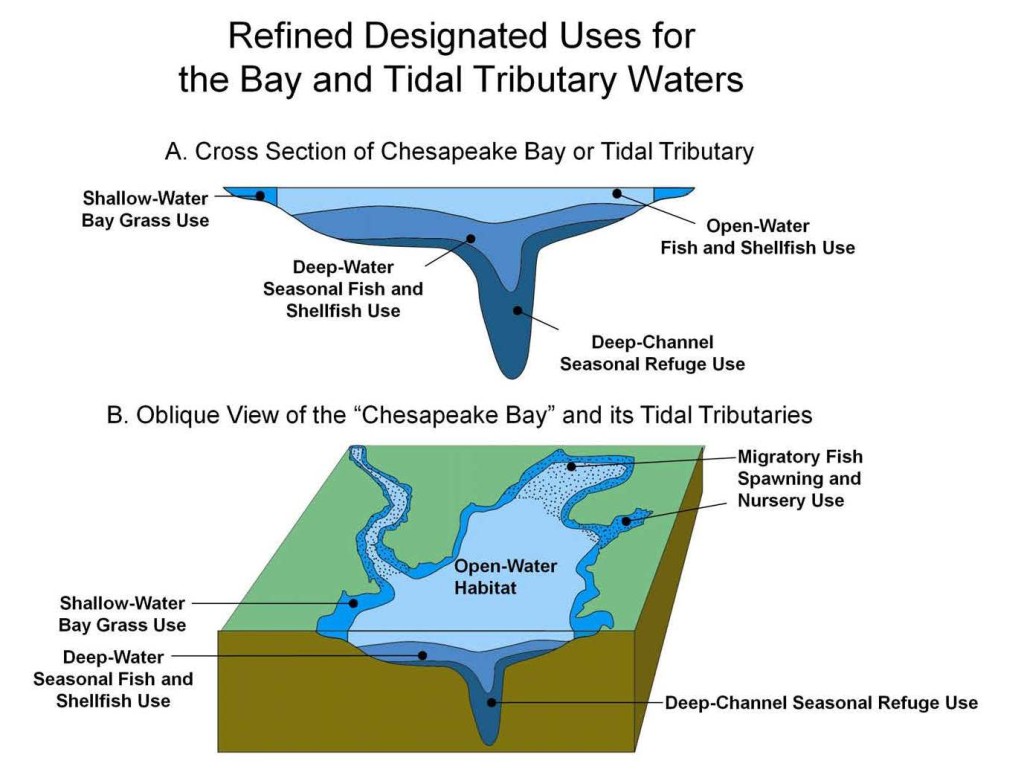

Chesapeake Bay Tidal Water Designated Uses

EPA and the seven Bay watershed jurisdictions have agreed on five refined aquatic life designated uses reflecting the habitats of an array of recreationally, commercially, and ecologically important species and biological communities. The five tidal Bay designated uses are applied, where appropriate, consistently across Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia’s portions of the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributary and embayment waters. The Bay TMDL designates the following uses for the Port Tobacco River:

- Migratory fish spawning & nursery (Feb. 1- May 31)

- Open water fish & shellfish (Year-round)

- Shallow water Bay grasses (SAV growing season)

The two remaining tidal Bay designated uses (deep-water seasonal fish and shellfish, and deep-channel seasonal refuge) apply to habitat conditions that do not exist in the Port Tobacco River.

Water Quality Criteria

The Bay TMDL establishes water quality criteria for dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll a, water clarity, and submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV). These criteria are set at levels to prevent impairment of growth and to protect the reproduction and survival of all organisms living in the open-water column habitats.

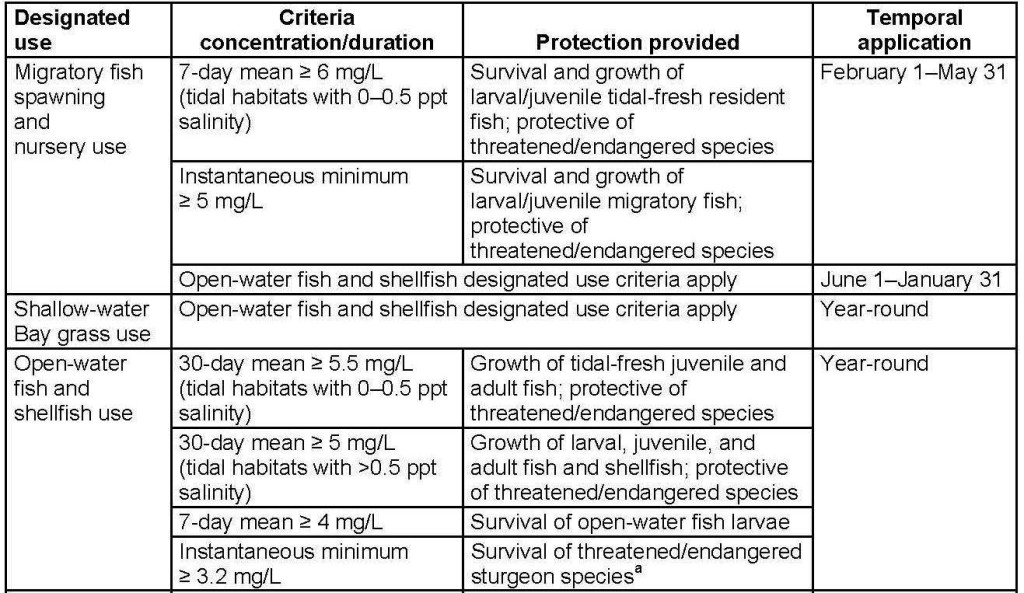

Criteria for Dissolved Oxygen

Oxygen is one of the most essential environmental constituents supporting life. In the Chesapeake Bay’s deeper waters, there is a natural tendency toward reduced DO conditions because of the Bay’s physical morphology and estuarine circulation. The Chesapeake Bay’s highly productive shallow waters, coupled with strong density stratification (preventing reaeration); long residence times (weeks to months); low tidal energy; and tendency to retain, recycle, and regenerate nutrients from the surrounding watershed all set the stage for low DO conditions. Against that backdrop, EPA worked closely with its seven watershed partners and the larger Bay scientific community to derive and publish a set of DO criteria to protect specific aquatic life communities and reflect the Chesapeake Bay’s natural processes that define distinct habitats.

Criteria for Chlorophyll a

EPA has established narrative criteria for chlorophyll a, which state that concentrations of chlorophyll a in free-floating microscopic aquatic plants (algae) shall not exceed levels that result in ecologically undesirable consequences—such as reduced water clarity, low dissolved oxygen, food supply imbalances, proliferation of species deemed potentially harmful to aquatic life or humans or aesthetically objectionable conditions—or otherwise render tidal waters unsuitable for designated uses.

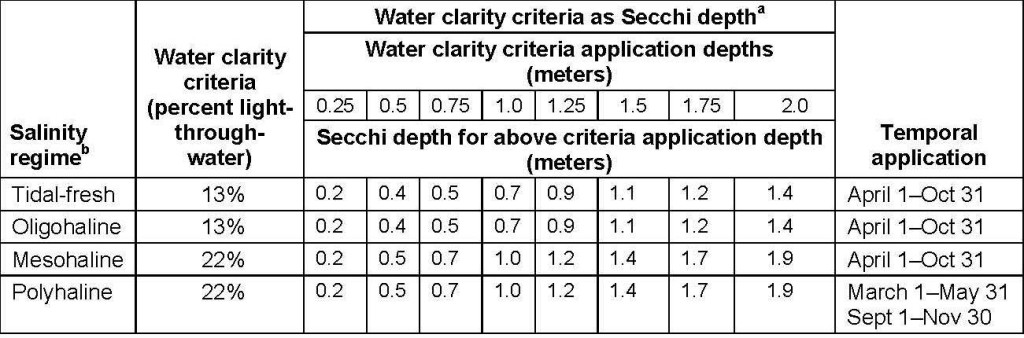

Criteria for Water Clarity

Underwater bay grass beds create rich animal habitats that support the growth of diverse fish and invertebrate populations. Underwater bay grasses, also referred to as submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), help improve tidal water quality by retaining nitrogen and phosphorus as plant material, stabilizing bottom sediment (preventing their resuspension) and reducing shoreline erosion. The health and survival of such underwater plant communities in the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries and embayments depend on suitable environmental conditions. The loss of SAV from the shallow waters of the Chesapeake Bay, which was first noted in the early 1960s, is a widespread, well-documented problem. The primary causes of the decline of SAV are nutrient over-enrichment, increased suspended sediment in the water, and associated reductions in light availability. To restore the critical habitats and food sources, enough light must penetrate the shallow waters to support the survival, growth, and repropagation of diverse, healthy, SAV communities.

Criteria for Underwater Bay Grasses

Underwater bay grass beds create rich animal habitats that support the growth of diverse fish and invertebrate populations. Underwater bay grasses help improve tidal water quality by retaining nitrogen and phosphorus as plant material, stabilizing bottom sediment (preventing their resuspension) and reducing shoreline erosion. The health and survival of such underwater plant communities in the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries and embayments depend on suitable environmental conditions. The Bay TMDL established a Bay-wide SAV restorationgoal of 185,000 acres and Bay segment-specific acreage goals. For the Port Tobacco River, the goal is the restoration of 262 acres of Bay grasses.

Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay Water Quality Criteria

Maryland has adopted into its WQS regulations all the EPA-published Chesapeake Bay criteria, assessment procedures, and designated uses documents. These Water Quality Standards apply to all Chesapeake Bay, tidal tributary and embayment waters of Maryland, all of which are subject to the Chesapeake Bay TMDL. Maryland has also adopted EPA’s narrative chlorophyll a water quality criteria.

Standards for Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Sediment

The Bay TMDL establishes annual total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and total suspended solids (sediment) allocations for the watershed areas draining to each of the 92 Chesapeake Bay segments, including the Port Tobacco River, necessary to meet water quality standards for dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll-a, water clarity, underwater Bay grasses. The Bay TMDL is designed to ensure that by 2025 all practices necessary to fully restore the Bay and its tidal waters are in place, with at least 60 percent of the actions taken by 2017.

The following are the standards for the Port Tobacco River segment, with 2009 levels in parentheses.

- Total nitrogen (lbs/yr): 128,036 (121,907)

- Total phosphorus (lbs/yr): 9,358 (9,972)

- Total sediment (lbs/yr): 3,024,465 (3,509,912)

These annual standards for nitrogen and phosphorus are significantly lower than the average-flow annual standards established in the Port Tobacco River TMDL — 243,310 lbs/yr for nitrogen and 15,570 lbs/yr for phosphorus.

Watershed Implementation Plans

The Bay TMDL will be implemented through Watershed Implementation Plans (WIPs), which detail how and when the seven Bay jurisdictions will meet pollution allocations. EPA will conduct oversight of WIP implementation and jurisdictions’ progress toward meeting two-year milestones. If progress is insufficient, EPA will utilize contingencies to place additional controls on federally permitted sources of pollution, such as wastewater treatment plants, large animal agriculture operations and municipal stormwater systems, as well as target compliance and enforcement activities.

Maryland’s 2016-17 milestones for restoring the Bay include implementation actions, on-the-ground activities that will result in nutrient and sediment load reductions; and program enhancement actions needed to increase resources and improve the implementation processes to accelerate future restoration. A draft of Maryland’s Phase III Watershed Implementation Plan is available for public comment through June 7, 2019.

Charles County’s Phase II WIP Strategy outlines the restoration projects necessary to achieve the nutrient and sediment reductions required by the Chesapeake Bay TMDL. The projects are divided into sets of biennial goals, called 2-year milestones, which are tracked by the Maryland Department of the Environment. The County has released 2016-2017 Programmatic Milestones.